Housekeeping Tales & The Servant Problem

Jane would be a hoot to gossip with at any modern cocktail party!

But I’ve also always been fascinated, and somewhat disturbed, by an unwritten sub-text in all of Jane’s works….That is, the genteel world that she inhabited was only made possible by an army of invisible servants who did all of the dirty work, but these servants are only rarely mentioned in Miss Austen’s books.

They are not mentioned, because in real life the servant class in those days, and up until the 20th century, were considered beneath consideration. God made the world, and He bestowed money and wealth on the deserving. So poor people in turn deserved poverty, and they should be grateful for whatever bones rich people tossed.

It’s an interesting, if depressingly self- serving philosophy! And of course we see this still being played out today, as rich people demand that poor people get as few social services and government aid as possible. But I digress.

A really nifty book I came across is titled “Biting the Dust” by Margaret Horsfield. This book is a fascinating and witty history of house cleaning practices and how our tools and methods have evolved from Victorian times up to the present.

As in Jane Austen’s time, Victorian people of gentle social position simply did not do their own work. Even fairly impoverished families, if they were upper class, still managed to have cooks and housemaids to do the scut work. And in Victorian times, there was plenty of scut work to be done! Those draughty old mansions were heated with coal and wood, soot fell everywhere, and indoor plumbing was just coming into existence. Chamber pots to empty and cold water to clean with meant that a housemaid got up hours before the family to perform her endless tasks.

The servants’ quarters were usually up in the attic, and not heated. Larger homes frequently had a separate stair way for servants to use to preserve the illusion that they didn’t exist, and of course they were required to use the back door or servants’ entrance.

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, many girls were happy to get factory jobs, crappy as they were, because they did not have to work all hours for a household, lugging water upstairs and slop pails down.

Many magazines and books offered advice to mistresses on how to handle their servants. It’s unfortunate that most of the serving class were not literate, or maybe they just didn’t have the time to write, because only a couple of diaries written by servant women have been discovered. These are fascinating windows into just how hard their lives were….and there was no retirement pension waiting for them when they got too old to empty the chamber pots.

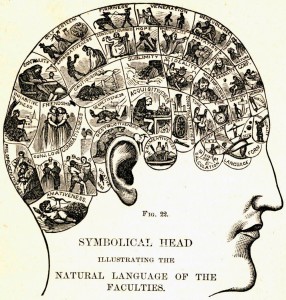

Whereas rich ladies had all the time in the world to write about just exactly how servants should work and behave. Most of this advice is utterly cringe inducing now! In 1899 an article in The American Kitchen advised mistresses to use phrenology to judge potential servants. “In choosing a servant, the article states, see that the applicant’s head extends back some distance behind the ears. This portion of the head is known as the ‘domestic region’ and where it is not well developed, a servant is likely to be unsteady and dissatisfied. See also that the bump of firmness on the apex of the head rises well above the region of self- esteem, directly behind it. Otherwise the servant may prove insubordinate, independent, and altogether unpleasant.” Mustn’t have any independence or insubordination from the servant classes!

Mrs Mary Eliza Haweis, in The Art of Housekeeping, wrote critically and tirelessly on how employers should judge and deal with servants. Writing in London in 1899, she does not beat around the bush. Servants, she says, are ‘no more like the gentry than dogs are like cats’. Compared to her gentle readers, ‘they are quite different flesh and blood’, and anyone who thinks or acts otherwise is clearly a fool.

It is the mistress’s duty, she says, to see that she takes control of these people. ‘Keep as few servants as you possibly can….give every servant plenty to do, and see that it is done; give them meat only twice a day, and no beer. For drinks… water, lemonade (which is cheap enough) or tea.

Young girls who normally worked as housemaids were underpaid, inexperienced, overworked and unappreciated. They were also usually lonely and far from home. Beginning a life as a housemaid at age eight was not uncommon, and these young girls had to enter service as their poverty stricken families needed the help.

As many girls sought employment at businesses, the gentry class complained loudly about the “servant problem.” Schools opened up to train young girls in household management so that they’d be more appealing to potential employers. And thus, the shortage of “good help” meant that mistresses had to treat their staff in a more considerate manner.

Reliance on servants to do the dirty household work was more widespread and lasted much longer in Britain than in America. Interestingly, the dependence on cheap domestic labour in Britain dramatically delayed the advance of domestic technology in that country. For example, the slow acceptance of central heating in Britain is directly connected the fact that there were so many girls trained to clean, set and light the countless inefficient open coal fires. It seemed an extravagant luxury to install heating systems to replace the cheap servants!

Keeping house today, even without coal fires, chamber pots and Victorian fripperies is still time consuming and laborious. Thank God for vacuum cleaners!

Stephanie Kelley